I was diagnosed with ADHD by a private clinic and all I got was this lousy ability to function

Stigma, gender perceptions, and accepting ADHD as part of my self-identity

About six weeks ago, on the same day the Panorama documentary “Private ADHD Clinics Exposed” aired, I was diagnosed with ADHD by a private clinic. This obviously came as little surprise by the time I got to the diagnosis – I had, after all, paid a private clinic which specialised in ADHD – but it took me a long time to accept that it was a diagnosis that fit for me.

My diagnosis of dyspraxia (also known as Developmental Coordination Disorder) in 2011 seemed to explain a lot of how I experienced the world, and the difficulties I ran into doing even very basic tasks like “washing up” and “getting to places on time.” Alongside the obvious movement and coordination difficulties, the Dyspraxia Foundation lists “Difficulty with organisation and planning” as one of the key diagnostic criteria. I certainly had a lot of difficulty with organisation and planning, and alongside my inability to catch a ball and delay in learning to ride a bike, I was decisively diagnosed. For a while, this truly did explain everything – not making friends, being forgetful, being disorganised – these were all dyspraxia things, right?

The more time went on, the more I realised I didn’t have the whole picture. I was using all the strategies I had picked up over the years and been taught at university, and I was more organised, but I was exhausted. And I was terrible at friendships, struggled in relationships, and often didn’t seem to know the “social rules” of situations. A failed attempt to get an autism diagnosis in 2017 followed, with the NHS Psychologist eventually, through gritted teeth (and after a complaint through PALS) admitting that he felt I was “near, but not over the line.” Apparently, I was just “too functional” to qualify for a diagnosis. This was intensely disheartening, and I became very frustrated by the limbo this left me in. Was I autistic enough to be in the online autism spaces I frequented? If I wasn’t ‘over the line’, did that mean I wasn’t actually autistic at all? To complicate things, I started working as an Autism Practitioner, talking about autism and working with autistic people every day. Always somebody who had been sure of my identity, I was in flux, and struggled with the lack of a neat box to fit myself into.

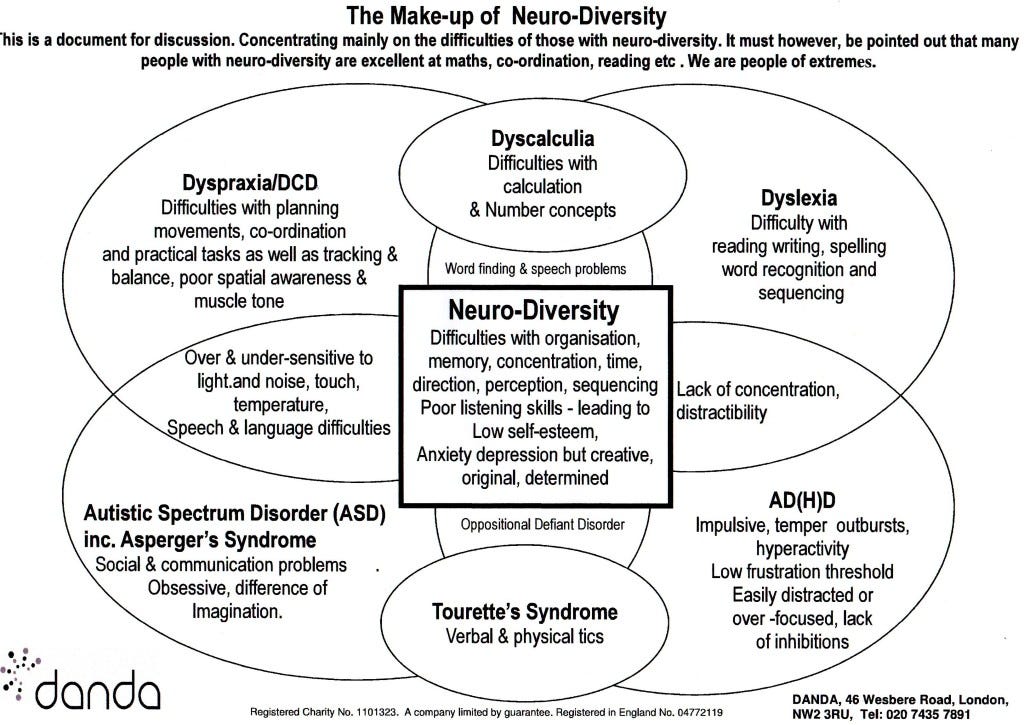

Fortunately, by this point I had been involved in the neurodiversity movement for many years, and was beginning to understand “neurodiversity is a spectrum” in a slightly different way. For years I had seen it through the DANDA model, a little like this:

The DANDA model is useful in bringing together the different neurodivergent conditions, but the Venn diagram format creates false crossovers and exclusions. The most pertinent thing here is that dyspraxia and ADHD are shown on opposite sides, without a specific crossover. And so, you could easily be persuaded that they were exclusive from each other.

Instead, I began to see neurodiversity as a collection of traits which differ from “neurotypicality”. Everybody who is neurodivergent has a good number of these traits, be they difficulties with organisation, lack of concentration, social difficulties, processing speed etc., and these can cluster into specific conditions, which is how we come to different diagnoses. However, there appears to be so many more crossovers and inter-relationships between the different diagnoses (I won’t use the word “disorder”, for my state of being is not “disordered”) than academic literature and common understanding gives credence to. And thus, it is possible to have significant traits of a neurodivergent condition, but not necessarily meet the criteria for diagnosis, which doesn’t even take into consideration the flaws and ableism present in the current DSM-V diagnostic criteria.

I’m impulsive. I have a long history of doing things without thought and thoroughly regretting them later. I’m also easily distracted and have a brain which seems to work at double the speed of everybody else’s – in the noughties era of “randomness” I was in my element – I was always bringing non-sequiturs into conversations because my brain had already skipped about 3 conversation topics ahead. I could tell you so many stories of how I was in trouble at school – from the time I got 3 ‘D-merits’ in one day because I forgot to change my shoes, lied about it, and then for some reason decided to draw on the floor when I dropped my pen – to when I was caught pinching chocolate fingers from the leftover Christmas party food and yelled at in front of the whole class. And this is before we even get to the fact I did no homework from year 8 to year 10, and never, ever had the right books unless I carried them all in my rucksack every single day.

Looking back at my childhood knowing what I know now, the ADHD is very obvious. It was, however, my experiences of other children with ADHD which created both an externalised, and therefore internalised stigma. I wasn’t particularly badly behaved, for a start. I had my moments, but on the whole I was the “goody two shoes” of my siblings. And I wasn’t hyperactive, in fact I was often very tired (turns out trying to prove yourself as a ‘functioning adult’ at all times is very tiring indeed). The boys, and it was generally boys, who had been diagnosed with ADHD at school weren’t like me at all. They were loud, they couldn’t sit still, they were always being sent out of the classroom. So, it had just formulated in my brain somehow that I should disregard everything to do with ADHD, because that didn’t apply to me. I saw myself in dyspraxia, I saw myself in autism (and there’s an irony here, because I have been an outspoken voice for the different presentation of autism in AFAB people), but I just didn’t see myself as having ADHD.

ADHD has historically been a stigmatised condition. Bart Simpson, for example, canonically takes Ritalin for ADHD, and is shown to be generally quite ‘naughty’. Travell and Visser (2007) studied the perceptions of ADHD in young people with a diagnosis and their parents and came to the conclusion that the stigma and negativity attached to the label far outweighed the benefits of “short-term treatment with medication”. Travell and Visser argue that in labelling ADHD, a broader “biological, psychological, social and cultural perspective” on poor behaviour is missed, and that young people instead come to see themselves as defective. This study came before the true explosion of the neurodiversity movement (something which is still only slowly making its way into the academic world), but the researchers showed an overall negative view of ADHD as a label, and thus they have created further stigma, and written a paper all about why it is a label of shame.

Olsson (2022) carried out a literature review of teachers’ gendered perceptions of ADHD, and found that whilst “behavioural issues” (for this is the lens we are still to view ADHD educationally) tended to be taken more seriously in girls, they were more often treated in boys. She also notes that teachers tend to view ADHD from a deficit perspective, and that the blame for behaviours associated with ADHD was always viewed as an “in-child” issue, and not something the school environment could address. This is a recent review of literature, and through the reduction of ADHD to difficulties regulating behaviour, and the unwillingness to change classroom environments, it is telling of the way ADHD is still viewed within education.

It is therefore, I suppose, not especially surprising that I didn’t see this as something that was relevant to me, a woman who already had something of an explanation for her difficulties. This was despite learning that women with ADHD tend to be more inattentive than hyperactive, or have ‘internalised hyperactivity’ (for example, my brain which never shuts up). When ‘ADHD influencers’ became a thing, I found the content extremely relatable, but worried this was because the experiences being put forth by the influencers were general experiences of the human condition, and not replicable and defined traits of ADHD.

It took my sister announcing that she was seeking a diagnosis for me to actually take the self-administered tests and consider my life as it had been up to that point. I scored highly on every screening test I took, and suddenly things began to make sense. Yes, neurodiversity was this amorphous blob of traits where you had some and not others, but perhaps there was a cluster of traits which added up to ADHD for me. And I was right. I was resoundingly diagnosed through the Diagnostic Interview for ADHD in Adults (DIVA) assessment (the same assessment used by NHS ADHD clinics). It took a bit of processing, and a bit of self-reflection even after the diagnosis had been given. I’d tilted my entire worldview of what ADHD was through teaching neurodivergent people, and by being part of the neurodiversity movement, but it still took time to orient myself into seeing myself through that lens.

I’ve since started taking medication, and my life is changed in small but incredibly helpful ways. Having always been an enormous procrastinator, I can now do tasks with little encouragement. I have focus and drive, and I’m so much less stressed, because I don’t have unfinished tasks and ‘things’ I really need to do hanging over me all the time. The medication – a small amount of amphetamines – has some unwanted side effects (some of which have sent me into a massive ‘but what if I don’t even have ADHD?’ spiral), but as I’ve adjusted to the medication and the new way of being, I can see that I am changed. My life is easier. It’s as simple as that.

At this present moment in time, in 2023, it feels like nearly everybody I know is getting an ADHD diagnosis, although the fact that I know most people from online sources of continual dopamine probably skews that data. And I must admit that I had become a little suspicious of the ease with which people were able to get a diagnosis. I think I will always have a little “but what if a private diagnosis doesn’t count?” voice in my head – despite my disastrous dealings with NHS diagnostic services (the biggest problem is that they are so siloed, but that’s a complaint for another day) – but in all honesty the results of the medication, in my test group of one, are speaking for themselves. And you don’t have to look very far for anecdata from other ADHD-ers who say the same.

I have formal diagnoses of dyspraxia and ADHD. I have been told I have ‘autistic traits’. I am, and will always be, neurodivergent, regardless of the medication I take. And I’m ok with that - because despite everything being a bit more difficult - it’s the thing which makes me uniquely who I am. We can be annoyed by the ‘ADHD influencers’ and admit that sometimes they are generalising an experience which is not unique to ADHD, whilst also recognising that they are doing some good. Getting a diagnosis and treatment for a very real condition genuinely changes your life. Anything which fights the stigma surrounding neurodiversity is, in fact, a very good thing.